Masters Of Design From Canada To The Caribbean

By Rajitha Sivakumaran

Guessing the one commonality between a Globe & Mail Home of the Week and a 200-year-old Caribbean villa is no easy task. The connection is the architect Paul Wright. Educated in the UK, Wright entered the field in the 1980s and now serves as the principal at ACI Wright Architects, a full-service architectural company that specializes in a number of different industries from commercial and industrial to hospitality and residential. The architects at ACI follow a project from start to finish—a process that can include finding a site, purchasing a site, initial design, obtaining building permits and construction administration—through to occupancy.

The firm’s role depends on the needs of the client, Wright said, and sometimes the client may request a transformation of an existing building so great that the final product may look nothing like the original.

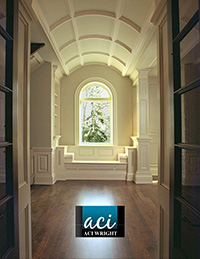

One client from Toronto’s wealthiest neighbourhoods requested Wright’s help in a grand scheme to completely transform his 1960s residence into an aged Georgian-style home.

Georgian architecture gets its name from the succession of English kings named George, popularized in the 1700s. The style is defined by symmetry, gentility, and elevated style. Its charm still endures along the eastern sea line of North America, where English affluence dominated high culture.

ACI designed every square inch of the house, a venture that took three years to complete and more than doubled the size of the home to 7,200 square feet.

“The client and I spent an incredible amount of time, designing right down to the keyhole of the cabinet in the library,” Wright said.

“It was an absolute treat to work on it,” Wright said. “Although the client had a clear vision of wanting an aged Georgian home, the challenge was converting the ’60s-modern style, very tight-knit home to look like an aged Georgian home. I think we were very successful in achieving that. What we strive for at the end of the day is to have clients who are extremely happy about the work we do after all this is who it impacts – they are the ones who live or work in our designs.”

Working in the Caribbean

Although Wright’s is licensed in Ontario, Manitoba and Nova Scotia. ACI’s operations in Toronto has also contributed to designs for a World Trade Centre in Oman and several lightweight concrete homes in South Africa.

“As we’ve grown, we’ve gone all over the place,” Wright said. “We’re not afraid to go far afield.”

The company went as far as developing a niche in the Caribbean when it restored a 200-year-old villa in Barbados. When Wright and his client arrived in Barbados, he was given the week to immerse himself in the history and culture of the area, an experience he described as a “huge eye-opener”.

“As with anything else, if you go to a different country or place… you have to learn about the local area, the history and the culture. Putting somebody’s building in there, you have to know where you’re fitting into that fabric of society,” Wright said.

Going into the project, Wright didn’t fully realized what a major undertaking it would become. The challenges of designing a building in the Caribbean proved to be quite unlike that of building in Canada. The salty air, for example, eats away all the metal in the building and termites can be a nuisance.

“You open up the wall and there’s no wood in the walls. The plaster is holding up the wall because the termites have eaten all the wood behind it,” Wright exclaimed.

Other challenges circle around money and the project Wright was involved in nearly a decade ago in Grenada is a good example of this. This long-term-stay, apartment-style building was innovative from the very beginning and was designed to incorporate modern green technology. ACI designed a rainwater collection system off the roof due to water shortages during the dry season. The building was also equipped with solar hot water technology.

The project was initially supposed to go into construction in 2008, but when the economy crashed that year, banks stopped lending, and progress was halted. With funds now renewed, the project is soon expected to enter the construction phase.

Something a little more erratic than capital availability is nature itself and this can be particularly troublesome when working in the Caribbean. Although Grenada is south of the hurricane zone, it was hit by two hurricanes in a single year, prompting the incorporation of weather-resistant architecture. Wright has witnessed the devastation caused by hurricanes himself, having been on the island after Hurricane Ivan had ravaged through.

“We’ve done our best to design for hurricanes, storms that may hit once every 40 years, as well as earthquakes,” said Wright. “Each place has a different challenge. You’ve got to be careful of the termites eating it, you’ve got to be careful of the salt destroying it and you’ve got to basically make it bullet-proof and then on top of that, you want it to live and breathe and have air go through it.”

Future trends: Energy consumption and the millennium generation

The biggest trends in modern architecture are revolving around energy consumption and the many challenges that occur in the streamlining of sustainable design in Canada.

“The challenge we have as architects is that we can push green technologies and designs,” Wright said. “But if the client doesn’t want to do it, that becomes a challenge.”

According to Wright, the government is forcing owners to rethink green design in terms of their carbon foot print, not just for operational savings.

“New building codes in Ontario are changing how owners think as we move to eliminating fossil fuels in buildings by 2030,” he said. “Most owners are currently unaware that buildings will be required to undergo Energy Audits which could add liabilities for owners even though the current Ontario Codes require Owners to be dealing with this.”

Unlike the European market where green technologies like solar energy have been around long enough that adoption and mass production have taken off, going green remains costly in Canada. LEED-approved buildings require architects and engineers to do more work which owners may not want to pay for.

“There are certain things we can all do with minimal costs that can improve reductions to energy consumption in buildings.” Wright said.

Utilizing passive design, which is nothing new like the careful placement of windows, for example, would prevent heat gain, designing for wind flow for natural ventilation rather than air conditioning. Stopping air leakage to prevent heat loss can also greatly minimize energy consumption from heating and conditioning.

These are just some building techniques that can be more sustainable, and more affordable, than LEED-quantified design.

Wright spoke candidly about green awareness in Canada. “Europe is much further ahead than North America in this,” he said. “So finding the right way to do it so owners still make money will be a result of the entire team being on board.”

Other industry trends include a fluctuation in the demands of the various sectors in architecture. At the moment, the hospitality sector has a growing niche for boutique hotels. Having worked with powerhouse hotels like Hilton, Marriott and Best Western as well as larger residences like the Georgian Home, ACI has naturally developed a niche in this market.

Wright expects new trends to emerge in the hospitality market as the older generation is replaced by the fascinations of the millennial generation.

“We’re going to see a very different style of hotels coming into the market, although one could argue they are reinventing past decade hotels,” Wright said. He’s thrilled to be currently involved in designing some of the first in Canada.

www.aciw.ca