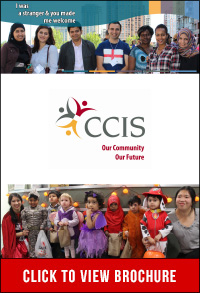

35 Years of Creating A Home Away From Home

By Rajitha Sivakumaran

For the first time in nearly 150 years, Canada’s population had more individuals over the age of 65 than children under 14 years last year. The population has been aging for some time and the consequences of this are many, but one in particular is critical: an aging workforce.

For the first time in nearly 150 years, Canada’s population had more individuals over the age of 65 than children under 14 years last year. The population has been aging for some time and the consequences of this are many, but one in particular is critical: an aging workforce.

Immigration is one of the most competent ways of mitigating the effects of the declining Canadian-born labour force. Canada already has one of the largest per-capita immigration rates in the world, but the new Liberal government has elected to increase that amount to 300,000 in 2017. This policy will not only strengthen the economy, but will put Canada at the forefront for talent acquisition.

But bringing in highly qualified immigrants is only the first step. According to the Immigrants in the Labour Force report released by the Government of Alberta, immigrants made up 25 per cent of unemployed Albertans in 2015. Established immigrants, however, had an unemployment rate that was lower than the provincial average. So how do you become established?

That has been the mandate of the Calgary Catholic Immigration Society (CCIS) since 1981. As a non-profit organization that helps immigrants and refugees settle in Southern Alberta, CCIS has witnessed countless success stories over the years. The organization itself is a grand success story. This year, the group is celebrating its 35th anniversary.

CCIS started with only a handful of volunteers led by the church in the 1970s just as Vietnamese refugees were coming into Canada. About 60,000 refugees arrived from Vietnam, but there was no support system in place to integrate, settle, support, educate, train and employ these people. Receiving no support from the federal government, the volunteers approached the Bishop of Calgary, who gave them $20,000. The government, in turn, matched this amount. With a tidy sum of $40,000, the founders launched what is known today as the Calgary Catholic Immigration Society.

“We were created because community saw a need,” said Fariborz Birjandian, CCIS’s CEO for the past 22 years. “We are here to solve a social problem.”

As with many charitable groups, a continuous source of funding was a problem in its early days, which was why CCIS took an entrepreneurial approach and opened a daycare facility.

“Coming from a technical and entrepreneurial background, I try to include many of those concepts into what we do. I always feel that we are no different from any other business,” said Birjandian. He operates CCIS as a mandate-driven organization, rather than a fund-driven one. Although partnerships with the federal government are a major source of funding for CCIS, the organization is continually diversifying its funding.

Today, as the fourth largest immigration service agencies in Canada, the organization is worth $30 million and operates out of three buildings in Calgary, all of which it owns. Its various departments specialize in everything newcomers need to integrate themselves into Canadian society successfully. From family and children’s services to business, employment and training programs, this organization has 300 employees and 1,500 volunteers who help not just immigrants, but refugees, seniors, temporary foreign workers and youth.

Job readiness is an important focus at CCIS. With nearly 5,560 industry partners, the organization has connections to sectors like energy, oil and gas, engineering, construction, manufacturing, service and retail. The good news for employers is that CCIS has an extensive database of professionals. Between 2009 and 2014, 12,000 newcomers with experience and expertise in specific trades partook in CCIS’s Business, Employment and Training Services division. In 2014, CCIS conducted about 5,900 hours of trades training instruction.

The man at the helm of CCIS

When Birjandian joined the group in 1988, the organization had grown to about 40 people. As a refugee himself, Birjandian is no stranger to the difficulties of settling in a new society. In fact, his life prior to arriving in Canada echoes the agonizing stories of many newcomers. He was a naval officer in the Iranian Navy, his wife a high school teacher. After the revolution, he and his wife lost their jobs and were prejudiced for being Baha’i, and harsh treatment and persecution ensued for a few years. Eventually, the situation worsened enough to make the Birjandian family flee to Pakistan.

Luckily, having studied and worked in Pakistan previously, Birjandian was already familiar with the culture. He soon became involved with the United Nations High Commission for Refugees. Once he arrived in Calgary, Birjandian volunteered with the Red Cross, developing a program called Support for Survivors of Torture. He donated his time to CCIS too and was eventually hired as a counselor. When the organization opened a new division called Business Improvement and Training Services, Birjandian was hired to manage it. Four years later in 1994, he made his way to his current post as CEO.

Multicultural, multilingual and multidisciplinary

Despite the name, CCIS is not part of the Diocese of Calgary. Although it began as a church-led movement, the group is multicultural, multilingual and multidisciplinary, and helps newcomers regardless of religion. Out of a staff base of 300 people, about 10 per cent are Catholic. The rest are Muslim, Jewish, Baha’i or other faiths, and come from 120 different countries and speak over 60 languages. Accordingly, CCIS board contemplated a name change many times, but eventually ruled against it. The name is a reflection of the organization’s past, said Birjandian.

Despite the growth and success of CCIS, running a non-profit organization is not without challenges. Birjandian cites two main sources: managing newcomers’ expectations and community expectations. Immigrants have invested a lot of money and resources to come here, he says, adding, “They come with a lot of hope, but it is not easy to settle here. This is a knowledge-based society, a beautiful environment, but the people coming here have no social capital.”

Standards of living are very high in Canada; cars and cellphones are commonplace possessions. Furthermore, the cost of living is rising. Immigrants have to hastily integrate themselves into the labour market and earn money to survive. “Managing their expectations, being responsive to these needs and making sure that CCIS programs relate to them is an ongoing challenge,” Birjandian said. Last year alone, CCIS, alongside the Diocese, sponsored and settled 900 refugees.

On the other side is community expectation. In Birjandian’s experience, communities expect newcomers to arrive and quickly become taxpayers. CCIS is constantly communicating with communities to help them understand the complexities of the integration process while simultaneously creating welcoming environments that set immigrants up for success.

So far, CCIS has been managing quite well. This year it was the recipient of the City of Calgary Award: Community Advocate Organization, something that Birjandian is very proud of. “If we want to stay faithful to our roots and make sure that the mandate that we have is not lost during funding conversations, then being recognized as an organization that is not giving up on advocacy is very good for us,” he said.

There is no doubt that immigration is going to be more prominent in Canada, which means that there is a real need for the type of services offered by organizations like CCIS. Over the next five years, CCIS will be focusing its initiatives on providing opportunities to the most vulnerable.

www.ccisab.ca