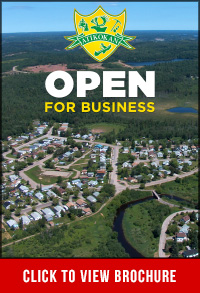

Open for Business

By Rajitha Sivakumaran

The town of Atikokan, now 117 years old, was founded as a stop for the Canadian Northern Railway, but few know that this small mining town in Northwestern Ontario played a pivotal role during the Second World War. From 1940 to 1978, there was a significant amount of iron ore mining that took place within the boundaries of Atikokan; two very large iron ore mines were developed there, but the process was anything but simple. The deposits were located at the bottom of a lake and could only be accessed if the lake were drained.

The town of Atikokan, now 117 years old, was founded as a stop for the Canadian Northern Railway, but few know that this small mining town in Northwestern Ontario played a pivotal role during the Second World War. From 1940 to 1978, there was a significant amount of iron ore mining that took place within the boundaries of Atikokan; two very large iron ore mines were developed there, but the process was anything but simple. The deposits were located at the bottom of a lake and could only be accessed if the lake were drained.

The project took place at a time when the Allied Forces needed the iron ore to produce steel for the military, but the undertaking was an expensive one. In fact, it required an act of the U.S. Congress to put in place the finances to develop it. Through many dams, tunnels and diversions, the lake was drained. Until the Three Gorges Dam was opened in China in 2003, Atikokan remained the home of the largest inland engineering project in the world. Furthermore, the mines generated enough iron ore to produce every steel part in every automobile ever manufactured in Canada.

“Historically, Atikokan has made a significant contribution to the development of Canada and to the creation of Canadian wealth and jobs throughout this country,” said Garry McKinnon, executive director at the Atikokan Economic Development Corporation.

The town was strongly entwined in the mining business, which was why when the mines closed in the early 1980s, Atikokan underwent several decades of economic dormancy. In the 1970s, Atikokan had the highest per capita income and the highest birth rate in Canada. The population was approximately 7,600 people, but the mine closures resulted in a loss of 1,800 jobs. The population immediately dropped to around 5,000 within an 18-month period, and the decline continued until another 50 percent of the population was lost.

Although the economic erosion was an ongoing occurrence, it was a gradual one. The community continues to have a modern hospital, which is currently undergoing some expansion. It is also home to a very good education system with a high percentage of graduates pursuing post-secondary education. Excellent recreational and protective services additionally aid the quality of life here. “We offer amenities that I would argue no town of our size is able to offer people,” McKinnon said.

Keys to success: industry, government and community

How has Atikokan managed to thrive despite the demolition of its key economic engine?

The town happens to be awash with natural resources. Mayor Dennis Brown, former elementary school teacher and mayor of Atikokan for 20 years, points specifically to forestry. When Resolute Forest Products opened its new mill, 90 direct jobs were created. Rentech’s mill, which makes wood pellets, contributed another 40 jobs. Public infrastructure like the town’s hospital employs over 100 people. So jobs are not lacking in this town.

In recent years, things have taken on a fresh perspective. McKinnon has noted a population increase in the last three or four years. Economically, new strides have been made too. The abandoned iron ore mines are now a target for the development of a very innovative energy project. The town is working with its First Nations partners in addition to engineering and financial firms with visions of creating a 1,200 to 1,300 megawatt battery for the storage of energy — an endeavour that is predicted to cost as much as $2 billion.

The town hasn’t completely lost touch with mining either. Canadian Malartic, a mining company, has identified 14 million ounces of gold at the Hammond Reef site in Atikokan. About $250 million has already been spent by the company pursuing this venture. Commercializing this large deposit will become a profitable reality when the price of gold bounces back up, McKinnon said.

The town’s success is also attributable to a stubborn determination to excel and communal loyalty. Mayor Brown and McKinnon spoke of two inspiring stories. Before the facility presently used to burn wood pellets was converted for such a purpose, it sat abandoned and close to demolition. It was the site of a particleboard mill, an industry that had crashed when importing from Indonesia and China had become more feasible. The municipality stepped in, maintained the facility and eventually recruited Rentech, the company that would ultimately build the pellet mill and employ up to 70 people.

“It demonstrates a degree of creativity, imagination and willingness to take some risk in order to promote business and the economy of the community,” McKinnon said.

Currently at the top of the mayor’s to-do list is infrastructure improvement, like upgrading the arena and swimming pool that were built in the early 1970s. “We had to come up with 5.5 million dollars,” the mayor said, adding that the town is still waiting for $1 million in funding from the federal government, through FedNor, an economic development program catered towards Northern Ontario.

In addition to help from the provincial government, the residents of Atikokan singlehandedly raised close to $600,000 for this initiative. “If you think about raising $600,000 from a community of 2,800 people, that is unimaginable!” McKinnon said.

The Canoeing Capital of Canada

Atikokan has another name — the Canoeing Capital of Canada — a name that reflects both the town’s past and present. The whole area of Northwestern Ontario was opened up and developed by the canoe. The town sits on the original fur trade routes that connected Montreal to Western Canada, and Native inhabitants and trappers commuted via canoe to trade at various trading posts throughout the region.

In more recent history, canoes played an essential role in the rise of Atikokan’s gold mining industry. Between 1890 and 1920, there was an estimated 50 operational gold mines. “All of that prospecting and development was essentially done by people in canoes,” McKinnon explained.

Canoeing also plays a significant part in the recreational culture of the residents of Atikokan, who use it for hunting and fishing. More recently, canoes have been used to explore what Mayor Brown called one of the jewels of this area — Quetico Provincial Park. The park is the only true wilderness park in Ontario where no motorized access is permitted. “The only way you’re going to explore the magnificence of that huge landscape is by canoe,” McKinnon said.

To facilitate this, Atikokan is home to many canoe outfitters. One of the largest canoe manufacturers in Canada, Souris River Canoes, moved to Atikokan in the early 1990s from Manitoba. At that time, they were producing about six canoes a year; they are now producing between 450 to 500 canoes in Atikokan.

“The Canoeing Capital of Canada is a safe, healthy community with a diverse economy, strong ties to the wilderness and a creative spirit,” Mayor Brown said.

www.atikokan.ca